Marvellous Moustaches & Superpowered Sea Floofs

Dr. Simon J Pierce is a co-founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, where he leads the global whale shark research program, and an award-winning marine wildlife photographer. About Simon.

A 10 cm goldfish, swimming through the water at leisure, leaves a wake that persists for over five minutes. Imagine if a fish-eating animal could detect and track that turbulence. It’d be one unlucky goldfish.

Seals, which are basically Jedi, are way ahead of me.

Australian sea lion at Jurien Bay, Western Australia

Lots of mammals use body hair for motion detection. Cats use their whiskers to identify objects in darkness, but these sensitive hairs can even detect changing air currents in a room. Useful if an obnoxious, cat-bothering child is silently on the prowl.

Underwater, this ability can be even more helpful. Whiskers, known as vibrissae, are present in animals as diverse as hippos, river dolphins, and sea otters.

Seals, the best-studied of these groups, have the largest “mystacial vibrissae” of any mammals. These luxurious mustaches grow to at least 41 cm in length and are vital to their hunting in low visibility.

Each whisker on a seal contains around 1000–1600 nerve fibers. That’s about ten times more than found in rats or cats. The vibrissae are extraordinarily sensitive. Seals can discriminate between objects of slightly differing sizes as well as monkeys can with their hands.

Check out the mystacial vibrissae on that!

All three families of seals use their whiskers to find food. “Eared seals”, the fur seals and sea lions, have a relatively sleek look, allowing them to live harmoniously in groups. (There may be more to seal social life than facial hair, but whatever. Call me judgemental.)

In contrast, walrus proudly maintain full hipster beards that would have been better left in 2012. While the pogonophobic Ross seal only has around 15 whiskers on each side of their snout, walrus have around 700 in total. These vibrissae, which form a dense beard underneath their mouth, help them to find and feed on buried shellfish in Arctic waters.

This is clearly excessive

Walrus produce a hydraulic jet of water to excavate clams. That stirs up so much sediment that vision becomes useless – and the point of their beardiful appearance becomes clear. Their whiskers can determine the size, shape, and texture of buried clams so fast that a walrus can find and inhale around six clams per minute.

“True seals”, such as common seals and elephant seals, tend to live a more solitary life. This may be because their prominent handlebar mustaches are a social disadvantage. They too have exceptional sensory abilities. Even blind seals have been seen in good condition in the wild, indicating that they can hunt effectively with their whiskers alone.

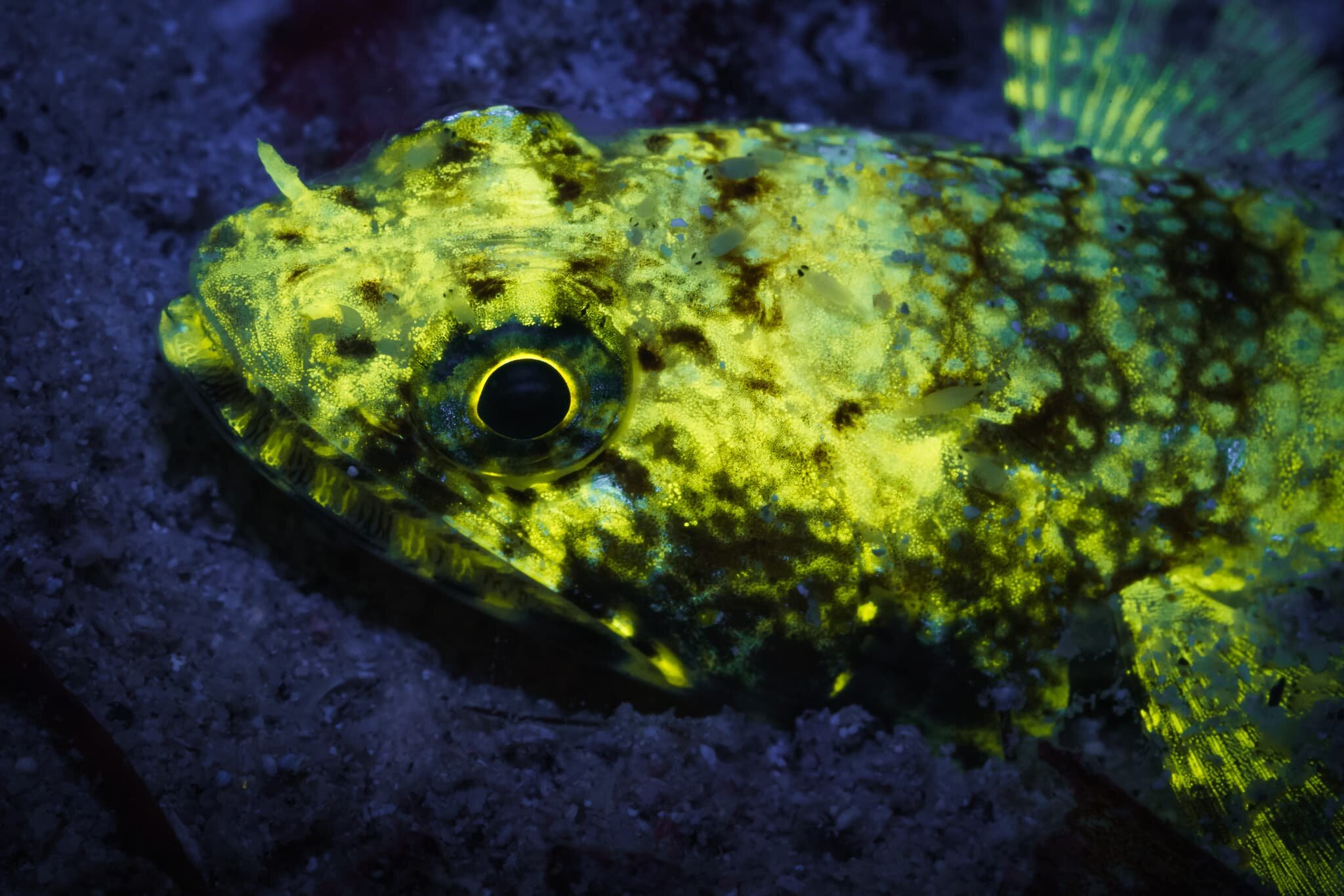

So floofy.

Streamlined though they are, fish can’t help but move water. Seals can follow simulated fish trails of at least 40 meters. Elephant seals, which feed on mesopelagic fishes, use their vibrissae to identify and hunt in the permanent darkness at over 500 m depth. Common seals can detect the gentle breathing of camouflaged flatfish, well-hidden in the sand. Of course, as life underwater is a constant evolutionary arms race, many fish respond by holding their breath when they sense danger.

Seals themselves also produce a wake when they swim. The ability to follow their mother’s trail is critical for seal pups as they learn how to forage. Common seal pups typically hold their breaths for about 1.5 mins, far less than their mothers. Being able to track her movements allows them to rejoin her at depth.

The usefulness of seal mustaches has not gone unnoticed by industry. Several research groups are building whiskered robots for object identification on land or wake detection underwater. Obviously, this would be useful for the military; they could detect stealth submarines or other vessels from their wake alone.

While their long vibrissae may lead to a bad case of resting itch face, seal mustaches are a fan(tache)tic adaptation to their environment. While hipster beards may never grow on me, they are clearly critical to the group’s success as aquatic predators.

Simon.