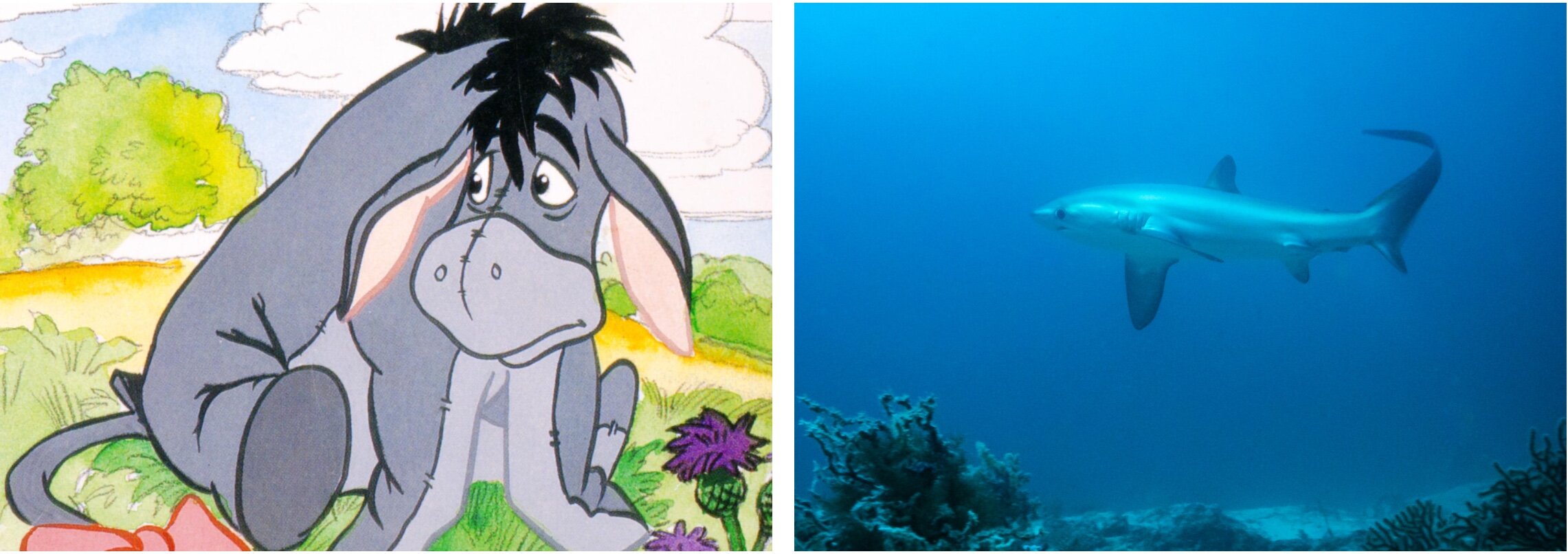

The Thresher Sharks of Malapascua Island, Philippines

Dr. Simon J Pierce is a co-founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, where he leads the global whale shark research program, and an award-winning marine wildlife photographer. About Simon.

Thresher sharks are one of those animals, like flying snakes or walrus, that are obviously made up.

Except they aren’t.

Thresher sharks are big. Common threshers (Alopias vulpinus), the largest of the three species, grow to about six meters (20 ft) long.

What’s unusual is that, like a royal wedding dress, half their length is tail.

Somehow, they make this look graceful, rather than like they’re accidentally dragging toilet paper around.

Malapascua Island in the Philippines is the best place in the world to see thresher sharks (which are sometimes known as thrasher sharks). From here, divers can reliably see pelagic thresher sharks (A. pelagicus) almost every day.

Pelagic threshers, though actually the smallest member of the thresher family, still reach over three meters in length. Rather than being intimidating, though, they’re adorable. Seriously. Thresher sharks pose no danger whatsoever to people… and the permanently anxious expression on their faces makes them look like Eeyore.

However, this is a very human-centric perspective. Let’s put ourselves in the mind of a sardine.

From their outlook, threshers are deadly ninja sharks.

Thresher shark biology

Outside the Philippines, pelagic thresher sharks are rarely seen by divers. Most biological information on the species has come from fisheries studies. These sharks grow slowly, reaching adulthood at about 10 years in males and 13 in females, and live to at least 24.

Thresher reproduction is really interesting. Only two pups are born per litter, one from each uterus. The developing embryos have a unique way of obtaining nutrition. The mother continues producing eggs through her pregnancy, and these yolk-filled egg capsules provide food for the pups as they grow. This reproductive mode is termed oophagy, literally “egg eating”.

The pups are free-swimming at birth, and almost half the length of their mother, at 1.4 meters. One shark at Malapascua was even seen giving birth! There’s a photo of that here.

What’s so special about Malapascua Island for thresher sharks?

Contrary to popular myth, divers already know that sharks aren’t typically interested in people. In fact, many sharks purposefully avoid us. That’s why “shark dives” often use bait; they have to overcome this natural inhibition.

Monad Shoal, a large seamount off Malapascua Island, is a pleasant exception to that norm. The shoal hosts several thresher shark “cleaning stations”.

Cleaner fishes, in this case blue-streaked cleaner wrasse and moon wrasse, like to hang out on particular patches of reef. These “stations” are like a fish health clinic. Sharks accumulate nasty little external parasites over time. These can cause chronic disease, developmental problems, and issues with respiration if they attach to the gills. Normal wear and tear from the sharks’ active predatory lives also result in minor injuries and dead skin, which can lead to infection.

Specialist cleaner fish eat these parasites, and the dead tissue, providing a useful service to the sharks – while gaining an easy meal themselves. Everybody wins. The sharks know that, so when the threshers want to be cleaned they’ll lower their tail and circle over the station to signal that they’d like some attention (and that they, as a fish-eating shark, mean no harm). They’ll slow right down to make it easier for the small cleaners to do a thorough inspection.

The daily presence of sharks at these stations has enabled Dr Simon Oliver and the other researchers in the Thresher Shark Research and Conservation Project team, operating from Malapascua, to conduct almost all of the behavioral research published on the species done to date.

It also makes Monad Shoal a KICKASS dive site.

Diving with thresher sharks

I’ve been up to Malapascua twice now. I’ll definitely go again. It’s great.

I’ve dived with Evolution (and stayed at their Dive Resort) on both trips, and spent another few days with Fun & Sun Malapascua (staying next door at Little Mermaid) in 2016 on a sponsored trip with Tourism Philippines.

The island is great. The only challenge? The thresher shark dives are often… early. Painfully early. Like, 4.45 am early.

Why go through such punishment? Cleaner fishes get hangry, that’s why. They sleep overnight, then wake up with empty stomachs. The sharks are thought to get a better clean from these highly motivated little fishies, and the sharks seem to agree. Some cleaning activity does occur throughout the day, but the mornings are the best time to visit.

Monad Shoal is an Advanced dive because of its depth. The cleaning stations are on the edge of the shoal, so you’ll often be down to 25-30 m. While there can be strong currents during certain moon phases, it’s not a difficult dive. The water temperature is lovely – I’ve been fine in boardies, particularly with a warm top (i.e. my Sharkskin vest), as it’s like 28ºC or so (82ºF). Mmmmmmm.

Planning a trip? Don’t forget to purchase travel insurance!

We use World Nomads to insure us while we’re scuba diving, snorkeling, hiking, on safari, in the Arctic… whenever we’re out and about while overseas. We’ve written up a full article on why we like World Nomads here on the site.

I view diving with the thresher sharks at Malapascua as an excellent example of positive ecotourism that is helping to protect these globally-threatened sharks , while also benefiting the local economy.

Check out this great video, by my friend Steve de Neef, about shark ecotourism at Malapascua:

Happily, all three species of thresher shark were listed on Appendix II of CITES in 2017.

Shark diving provides around 80% of Malapascua’s income. However, increased tourism comes with its own pressures. Reef damage from divers and anchors destroyed several cleaning stations on Monad Shoal before mooring buoys were put in place for boats, and the remaining cleaning stations were roped-off to divers (see the above video).

Roping-off the cleaning stations may seem like an extreme measure, but it’s clearly justified (and still allows for fantastic viewing of the sharks). My last visit to Malapascua was in 2016. At that stage, some dive centers were not being selective enough in who they took to Monad Shoal. I personally saw divers, who clearly couldn’t control their buoyancy, destroying areas of the reef (behind the ropes, thankfully).

A great way to ensure that you’re choosing a responsible dive operator is to check out the Green Fins site.

Photographing thresher sharks

You’ll probably be visiting Monad Shoal early in the morning, just after sunrise, when it’s still quite dark underwater. You’ll likely be deep. And because the sharks are thought to be sensitive to light, no use of flash is allowed.

Not easy conditions for an underwater photographer, then.

My old camera, which I was using when I last visited (an Olympus OM-D E-M1), couldn't autofocus on the sharks in those conditions. There just wasn't enough contrast. To get around that, I switched to back-button focus, focused on a rock that was at approximately the same distance as the sharks were likely to be, then avoided touching the focus lever!

I'd suggest using Manual mode with around 1/100 or 1/125 sec shutter speed, the largest aperture you think you can get away with, and Auto ISO. You'll probably be using a high ISO. My Olympus used to really struggle above about ISO 1600, but my current camera (a Sony A7rIII) should do far better in those conditions, so I'm excited to try it.

I was using a Panasonic 7-14 mm lens when I was there, and had it at 14 mm (i.e. 28 mm full-frame equivalent) the whole time. The Sony 28 mm f/2 lens would probably be perfect, then, but actually I've got a second-hand Nikonos 15 mm (on a Sony adapter from Nauticam) that I'm dying to use...

Really, my main suggestions are to (1) stay for several days, (2) use Nitrox for an extended bottom time, and (3) consider diving a little later in the morning, when most of the first few boats are ending their dives, to get more light. Similarly, focus on the shallower cleaning stations. You might see fewer sharks, but you'll likely get better photos of the sharks that you do see.

If you want to learn or improve your underwater photography, I highly recommend Alex Mustard’s book: Underwater Photography Masterclass. It’s a fantastic guide to a rather technical subject!

How can you help conserve thresher sharks?

Well, diving at Malapascua is a great start! Unfortunately, though they’re protected at Monad Shoal – now that the area is well-patrolled for illegal fishing, and responsible dive operators are minimizing reef damage – these sharks are still being fished when they move away.

I’m not sure how active the volunteer program is for the Thresher Shark Research and Conservation Project at this stage, but check their website and Facebook page for up-to-date information on that. Save Philippines Seas and the Large Marine Vertebrates Research Institute, Philippines, are both doing excellent conservation work on Malapascua and in the region too. I’ve worked with LAMAVE on whale shark projects in the Philippines and helped with their shark monitoring at Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park. There’s a neat thresher shark project in Indonesia, too.

More broadly, the pressure on thresher shark populations comes from overfishing. If you eat fish, do be careful to source sustainable options. There are guides to good seafood choices in the United States from Monterey Bay Aquarium and Environmental Defence Fund, in the UK from the Marine Conservation Society, WWF offers guides for a bunch of countries, and Forest & Bird has created a guide to New Zealand seafood. The global standard for sustainability is Marine Stewardship Council certification, so you can check their site for up-to-date options too.

Good, good. But ninja sharks?

Oh yes. Ninja sharks.

Dr Simon Oliver led another study, at Pescador Island off Cebu (about 175 km south of Monad Shoal), that used underwater video footage to examine thresher shark hunting strategies for their preferred local prey, sardines.

Fish don’t like to be eaten. Even for fast-swimming sharks, chasing down their prey on a one-on-one basis is energy-intensive, and often results in failure. Schools of fish are far more attractive to a predator, but individual sardines clearly feel safer in numbers. However, this schooling behavior does have a downside: it places a large number of baitfish close together.

Several predators take advantage of this behavior. Billfish, such as marlin and sailfish, will swim in fast and slash their elongated bills from side-to-side…

… whereas sei whales just engulf them.

Thresher sharks have those long, sophisticated, not-at-all-like-toilet-paper tails, which they use like a catapault.

Frame-by-frame video analysis reveals the sharks’ strategy. They lunge forward, then use their big wide pectoral fins to hit the brakes. This stalls their whole body, allowing them to deliver an overhead tail-slap at measured speeds of over 20 meters per second (45 miles per hour). That’s so fast that the tip of the tail literally causes water to bubble.

This results in considerable splattage. Up to seven sardines were seen killed by a single strike.

So there we have it. Although threshers may look concerned in photos, it’s the small fish that should be worried. Ninja sharks.

Kinda like this guy:

Kinda.

Simon.