Why Whale Sharks Swim to Cancun for Spring Break

Dr. Simon J Pierce is a co-founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, where he leads the global whale shark research program, and an award-winning marine wildlife photographer. About Simon.

Whale shark feeding in blue water off Cancun, Mexico

Mexico, specifically the area north of Isla Mujeres on the Yucatan Peninsula, is the seasonal home of large numbers of whale sharks over the summer months. It probably offers the world’s most consistent sightings of whale sharks for tourists over the northern hemisphere summer.

But why are they there? And what do we know about them? As one of the worlds few specialist whale shark researchers, hopefully I can help provide some answers.

Whale sharks: Big, spotty, & hard to find

Whale sharks are immensely popular with divers. Its easy to forget that seeing a whale shark was, until recently, a once in a lifetime event. Only 320 sightings had ever been documented until the 1980s, even though these huge sharks are distributed from New Zealand to New York.

It turns out we just didnt know where to look.

Tropical surface waters are a biological desert. Sure, coral reefs are incredibly rich in life, but theyre isolated oases in a literal sea of nothingness. Whale sharks eat mostly plankton and, as the worlds largest fish, they eat a LOT of plankton. Most of the areas where seasonal whale shark tourism has developed, such as Ningaloo Reef in Australia or Mafia Island in Tanzania, host some major biological event that rings a loud dinner gong for whale sharks.

Whale shark with swimmer off Cancun, Mexico

Why do whale sharks come to Cancun?

It’s all about the fish eggs. Little tunny, a small tuna species that can produce up to 1.75 million eggs each breeding season, spawn offshore to the north of Isla Mujeres.

This relaxed little island, just a short ferry ride away from the mega-resorts of Cancun, draws in its own annual migration of marine tourists and underwater photographers hoping to see the whale sharks in clear, blue, oceanic water.

Although local fishers have known about this annual phenomena since at least the early 1990s, scientists and tourist operators only caught on more recently.

Rafael de la Parra, a Mexican whale shark scientist, first laid eyes on this offshore aggregation in 2006. Whale shark tourism was already burgeoning off Isla Holbox, an island off the north coast of the Yucatan, where whale sharks and manta rays often feed in shallow, green, plankton-rich waters close to shore.

Rafael and his collaborators organised five flights further out to sea that year, during which 480 whale sharks were recorded.

Aerial survey flight path (black line) off the coast of Quintana Roo, Mexico

That changed everything. Repeated flights over this area – known as the Afuera, which means “outside” in Spanish – have documented up to 420 sharks in a single survey. It is, by far, the world’s largest known whale shark aggregation.

Aerial photographs of whale sharks feeding at the Afuera aggregation in August 2009. Figure A was taken from approximately 600 m altitude and shows 220 whale sharks and 4 tourist boats. Figure B was taken from lower altitude and shows 68 whale sharks, 1 tourist boats and 2 pairs of tourists snorkeling.

One of the things which changed was the management requirements. Whale sharks are a protected species in Mexico, and the government created a special Whale Shark Biosphere Reserve in 2009. Unfortunately, legislation couldn’t keep up with the scientific results, and the Afuera zone was not included in the reserve.

Whale shark research in Cancun, Mexico

I’ve been studying whale sharks since 2005, initially in Mozambique and now around the world. Rafael, his wife Beatriz and myself were all invited to participate in a research project off Utila, Honduras.

Learning more about their work in Mexico, I was determined to check out this amazing natural event for myself.

Whale shark with swimmers off Cancun

Fortunately, an opportunity presented itself not long afterward. From 2013-16 I helped to host groups from Aqua-Firma, a specialist dive travel and ecotourism company, on Isla Mujeres each summer. Dr. Chris Rohner, my co-investigator at MMF, took over in 2017-19 (MMF Senior Scientist Dr. Clare Prebble is going in 2021).

We joined Rafael during peak whale shark season (July / August) to conduct research, take photos, and generally revel in the presence of the hundreds of sharks that use this area as their seasonal home.

Every whale shark has a unique pattern of spots. It makes each individual identifiable, in much the same way as a human fingerprint. A photograph of the flank can be used to identify any whale shark, anywhere in the world. However, that matching effort is a massive job. To speed the process, automation is required.

A serendipitous friendship between a software developer and astrophysicist, both of whom were interested in marine conservation, led to a solution. An algorithm used in the processing of Hubble Space Telescope images was adapted, and whale shark spots were used in the place of stars.

The Wildbook for Whale Sharks online database was born.

As of 2020, there are more than 10,000 individual whale sharks on the database. Photo submissions from both researchers and the public allow the movements of individual sharks to be tracked around the world, population sizes to be calculated, and increases or declines in sightings to be identified and investigated.

Vertical suction-feeding on tuna eggs off Cancun

Eggs, eggs, eggs. Nom, nom, nom.

The trillions of tuna eggs on the menu here may draw in whale sharks from all over the Atlantic. The Yucatan coast, including both the inshore and Afuera sharks, was the first region in the world to reach 1, 000 identified whale sharks. Fully 75% of identified whale sharks from the Atlantic Ocean have been sighted in this area. It has to be one of the highest densities of sharks occurring anywhere in the world.

The little tunny spawn overnight, and their eggs float gently upwards to carpet the surface. The sharks literally swim around vacuuming the eggs up, for hours at a time.

Once the days spawn has dissipated, the sharks switch their behaviour and swim deeper overnight. It may be that the sharks are dissipating heat following hours of swimming and exposure to the sun in the hot surface water.

Back of the envelope calculations reveal that an average-sized whale shark, surface feeding for 11 hours, would ingest 142.5 kg of tuna eggs. That represents around 43, 000 Kcal, equivalent to over 8 kg of Dairy Milk chocolate (I worked it out. And now I want chocolate.)

Shifting to cooler water overnight may also slow their metabolism, helping to maximise the absorption of this massive meal.

With that much food on offer, its no wonder that the sharks stick around. Rafael and his colleagues tagging work has found that some individual sharks stay in the area for up to six months each year, with most having finally left by late August to mid-October.

Research from 2003-2012 has also found that many sharks visited the Afuera repeatedly, with some returning for six consecutive years.

Where do the sharks go?

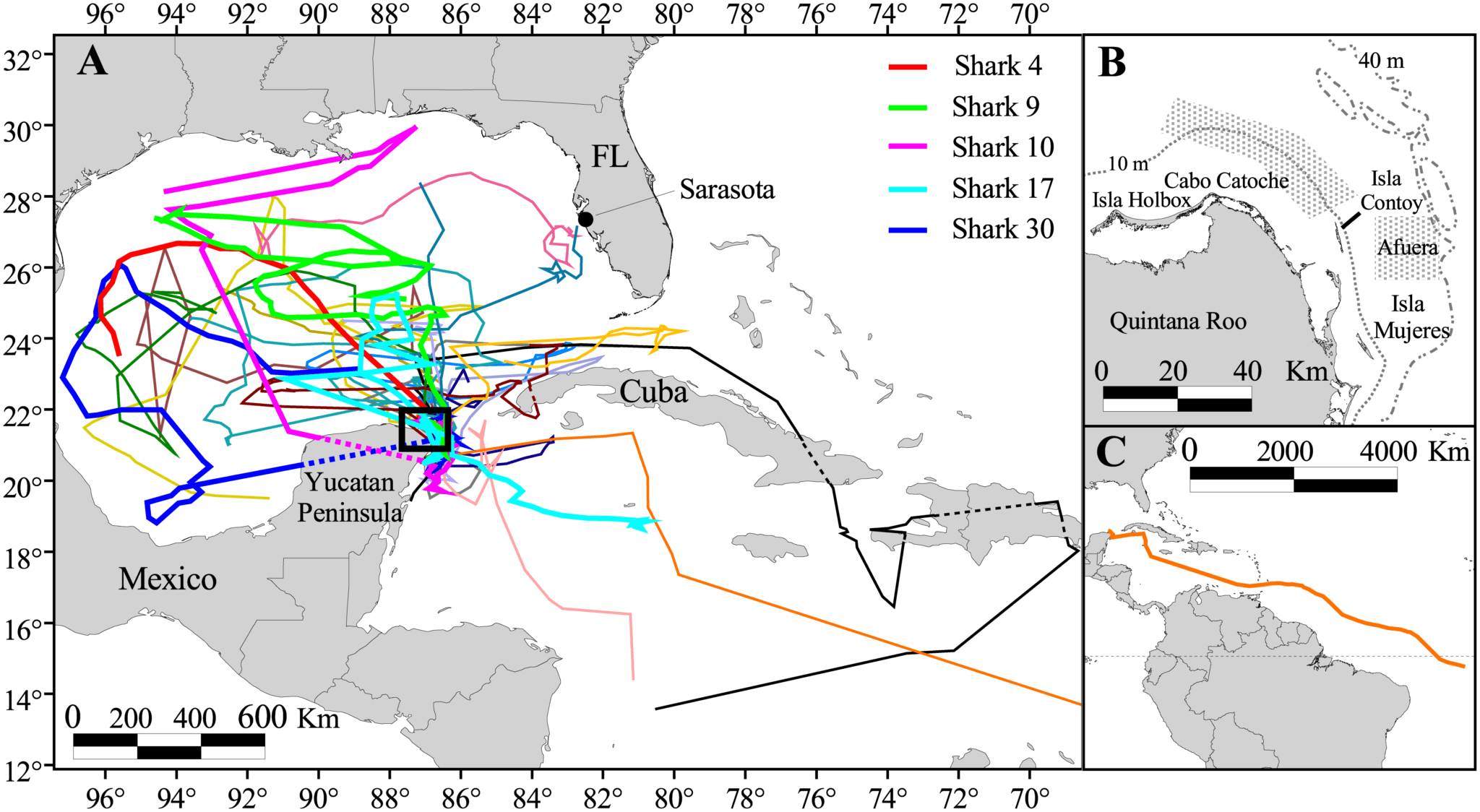

The most probable tracks for whale sharks tagged in the eastern Gulf of Mexico (A), including “Rio Lady’s” track (C)

Well, it seems to vary between individuals. Rafael and co-authors recently published a study on 31 satellite-tagged whale sharks from Mexico, which dispersed into the Gulf of Mexico or the Caribbean Sea.

When they moved away from land, and their reliable supply of tuna eggs, the sharks behaviours changed as well.

Because whale sharks are fish, they dont have to come to the surface to breathe. Although most of their time was spent near the surface, from 0 to 200 m depth, one of the tagged sharks remained at more than 50 m depth for three days straight.

Occasionally they dived much, much deeper, and the maximum dive by one of these sharks, 1,928 m, is the deepest recorded from a whale shark to date.

Its not easy to establish why the sharks are swimming so deep. There are a few potential reasons, or it could be a combination of several. A few clues were apparent.

Surface-feeding whale shark off Cancun, Mexico

Rather than occurring randomly, the deepest dives often occurred around sunrise and sunset. Increasingly, we suspect that whale sharks forage on deepwater zooplankton, which typically migrate between the surface at night and a few hundred metres deep during the day.

For the whale sharks, diving around these times may allow them to prey on the zooplankton during this migration, when some light is still available to make their hunt easier.

Deep dives could also have a navigational function. Dawn and dusk are when the earths magnetic field intensity reaches its peak, and – because the geomagnetic intensity gradient also increases with depth – these dives could help to improve their ability to determine their location.

Absent sharks & celebrity gossip

Whale sharks are born at around 50-60 cm, and may grow to 20 m. The Afuera aggregation is composed of mostly (72%) male whale sharks, ranging in length from 2.5 to 10 m.

The sharks present are predominantly juveniles: not babies, but few are reproductively active.

Where is the rest of the population? Well, somewhere else. Genetics work has shown that Atlantic whale sharks are a separate subpopulation to those found in the Indian and Pacific oceans, so we assume that the adults – and the majority of females – may live in the open ocean.

There isn’t a great deal of evidence to support that; its more that they are rarely seen along the coast.

The most probable track for “Rio Lady” on her journey south

One tagged female, thought to be a young adult, made a huge migration from the Afuera zone, across the equator into the mid Atlantic. This 7, 000 km swim, at an average speed of around 50 km per day, is one of the largest ever recorded for a whale shark.

This celebrity shark, now called Rio Lady, has been seen back at the Afuera since – in fact, Ive seen her each year since I first went there in 2013 – so this was a truly huge loop.

Rafael is fairly confident that she was pregnant when she was first tagged, although it is difficult to tell, so this single track is tantalising in that it could suggest that whale sharks give birth in the mid-Atlantic. Hopefully further work will provide more evidence.

Future challenges

It is a huge privilege for us to be able to swim with so many of these threatened sharks, and we all need to respect that the sharks use the Afuera for their own purposes. Their huge calorie intake of tuna spawn may help to fuel their movements for months afterwards.

Large container ship moving through the whale shark feeding area off Cancun, Mexico

The accessibility of the Afuera to day-trippers from Cancun means it does get crowded on the water, particularly during Mexican holidays, although the tour boats tend to be gone by midday.

It is a shame that the Afuera site was only properly delineated after the Whale Shark Biosphere Reserve was created, as this means the primary aggregation site is poorly protected.

Huge shipping vessels hug the tip of the Yucatan, coming dangerously close to the whale sharks and tourists. Although it is difficult to quantify, many whale sharks are likely killed on impact.

Propeller injuries on a whale shark off Cancun, Meixco

This shipping lane needs to be moved further offshore, for both the sharks and tourists safety.

Rafael, his wife Beatriz and their colleagues have formed a Mexican non-profit, Chooj Ajauil (Blue Realm in Mayan) to further the protection of this area.

Injury on a whale shark off Cancun, Mexico

After seeing up to 250 sharks in a day myself, I can truly say that this is one of the worlds most amazing wildlife experiences. The Afuera may be the best site in the world to see and photograph whale sharks. I hope you can make it next summer!

Further reading:

Follow Chooj Ajauil’s work on their website and Facebook page for the latest updates from the area.

Much of the information (and the scientific figures) in this article came from these three open-access papers:

Rafael de la Parra Venegas & co-authors: An unprecedented aggregation of whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, in Mexican coastal waters of the Caribbean Sea.

Robert Hueter & co-authors: Horizontal movements, migration patterns, and population structure of whale sharks in the Gulf of Mexico and northwestern Caribbean Sea.

John Tyminski & co-authors: Vertical movements and patterns in diving behaviour of whale sharks as revealed by pop-up satellite tags in the eastern Gulf of Mexico.